China’s economic challenges and emerging market bonds: no need for panic

China may be slowing down, but we believe that doesn’t diminish the opportunities on offer in emerging market debt. Here is why.

China is not only the second biggest economy in the world, it’s also the second biggest bond market.1 No wonder that when China sneezes, investors in emerging market (EM) bonds become nervous. But we believe there is no need for panic – for three key reasons.

For a start, China’s economic prospects are not as challenging as they first appear.

Although the real estate sector remains weak, there are some bright spots elsewhere. Domestic tourism is now higher than pre-Covid, and outbound tourism is now back to over 50 per cent of 2019 levels (which also benefits the rest of EM Asia, such as Macau, Hong Kong and Thailand). The service sector more broadly is holding up well and public investment is strong.

Chinese authorities have also been proactive in shoring up growth. They have reduced interest rates and provided support to the real estate sector. Mortgage rates have been cut by 150 basis points from the peak and this tends to impact borrowers with a lag, so the benefits have largely yet to materialise. At the recent Politburo meeting, authorities pledged to step up counter-cyclical measures, which could include plans to help young jobseekers and the easing of purchase restrictions to support the real estate sector. The Politburo meeting omitted the phrase "housing is for living, not for speculation purposes" – an important signal.

Economists have recently downgraded Chinese growth projections for 2023, with consensus expectations converging towards the official forecast of 5 per cent. Although this is lower than initial expectations (of around 6 per cent after a very strong rebound in Q1), it is still a marked improvement compared with last year.

This, in turn, should help emerging markets more broadly to retain an attractive growth differential relative to their developed peers – to the benefit of EM sovereign and corporate bonds.

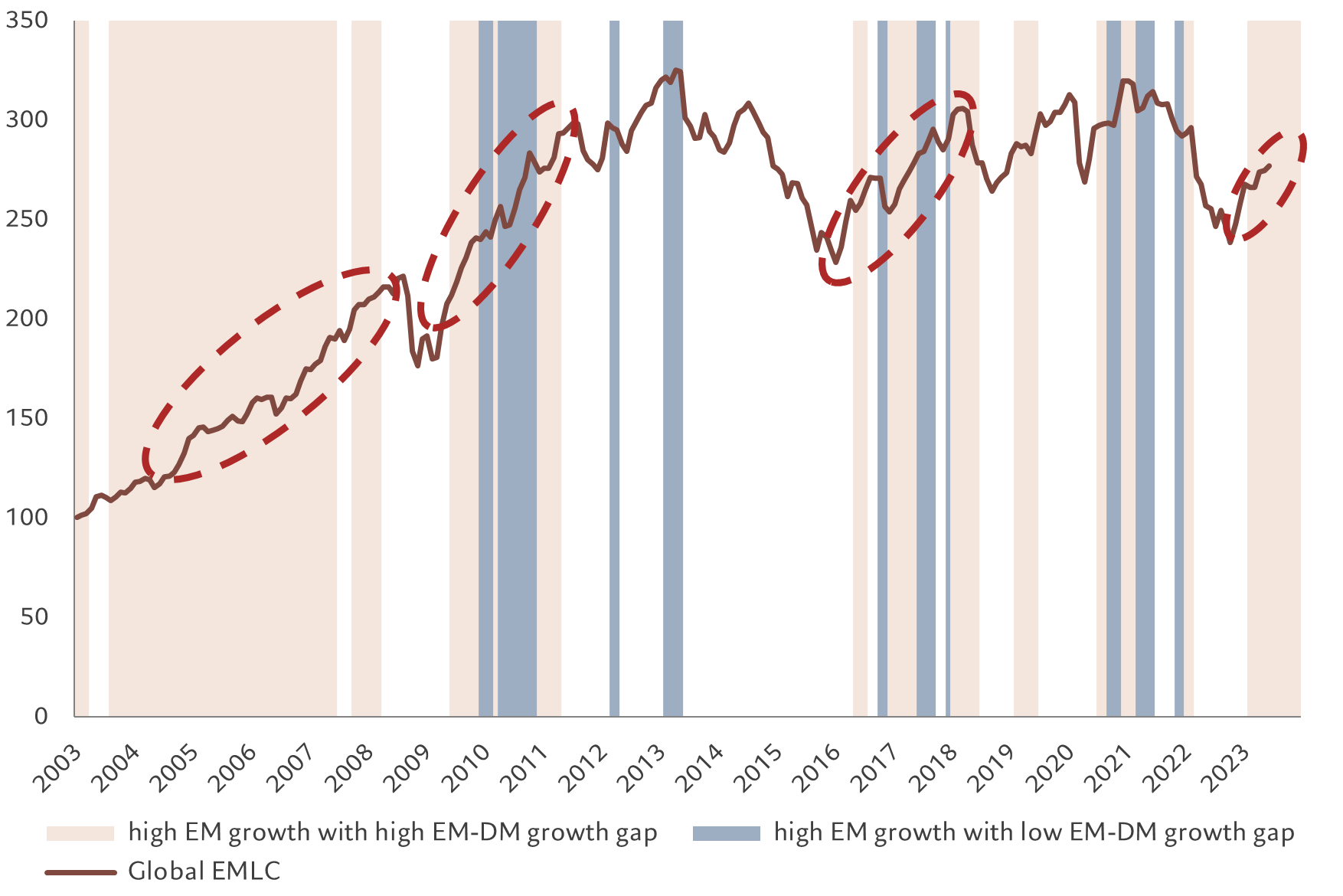

Source: Pictet Asset Management, CEIC, Refinitiv. December 2002=100. Data covering period 01.01.2003-27.07.2023.

We see the growth gap at around 4 ppts for this year and next. This is a sizeable buffer and thus, even if China’s growth was to fall short of current expectations, the growth gap between EM and DM would still be significant.

Our analysis shows that historically such a gap has been accompanied by the appreciation of EM currencies versus the US dollar and general outperformance of EM assets (see Fig. 1).

Fading dominance

Secondly, while China is clearly a very important part of the EM universe, its dominance is not as strong as it once was. The fate of other emerging markets has de-coupled from that of China in recent years in terms of both macro and asset class performance.

Different approaches to Covid-19 lockdowns and policy responses have resulted in diverging paths for growth, rates, and inflation. China locked down more severely than many other countries. It is thus only now recovering economically and has not seen the sharp rise in inflation witnessed almost everywhere else in the world, to varying degrees.

While other EM central banks, especially in Latin America, have proactively raised interest rates over the past two years, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) has stayed on an easing path to support growth. Now, other EM central banks are getting ready to ease monetary policy, which would potentially offer a huge boost for their local debt markets. Chinese assets won’t get such a marginal boost as the PBOC is already in easing mode, although its current monetary stance should be a slight positive rather than a hindrance to the general EM monetary easing theme.

The divergence also underscores decreased dependence of other EM economies on China through the commodity price link. Back in the 2000s, Chinese demand for commodities was a major boost for the developing world given the dominance of commodity exporters in the EM universe at the time. However, nowadays, EM is a much more diverse group and has a much more balanced ratio of commodity exporters and importers. Therefore, today’s lack of commodity demand from China is much less of a problem for the rest of EM than would have been the case 10 or 20 years ago.

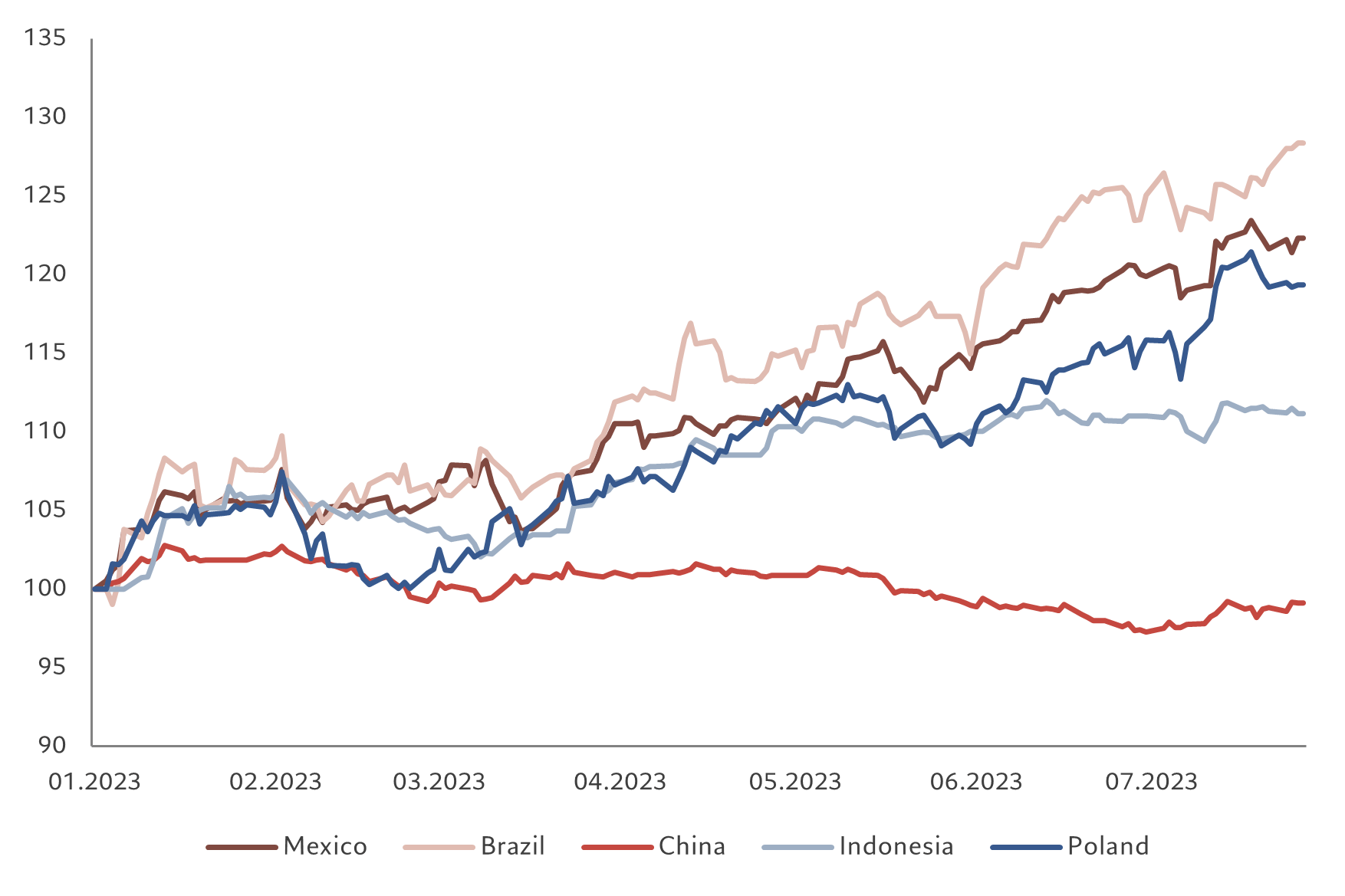

Source: Pictet Asset Management, Bloomberg, JP Morgan. January 2023 = 100. Data covering period 01.01.2023-27.07.2023.

Not surprisingly, markets are also differentiating between Chinese assets and those in other EM (see Fig. 2).

The JP Morgan Local Sovereign index, GBI-EM, is up 10.5 per cent year-to-date in USD terms, whilst its China sub index is down 0.7 per cent over the same period. This mirrors currency performance – while, for instance, LatAm currencies have rallied this year, led by the Brazilian real, the Chinese renminbi has lost 3.3 per cent versus the US dollar.2

Source: Pictet Asset Management.

Opportunities beyond China

Thirdly, we see some very positive developments across the developing world, which give rise to potentially rewarding investment opportunities.

Mexico is benefiting from companies shifting production closer to the US market. Real estate vacancy rates have dropped significantly in major Mexican cities, while asking rents are rising. Overall, we expect near-shoring to boost Mexican exports by almost 3 per cent of GDP through near- and medium-term opportunities. Similar trends are also at play in other Latin American countries. Some of this investment is being diverted away from China due to geopolitical tensions between Washington and Beijing. China’s loss, therefore, will be the gain of other EM economies.

India and Indonesia, meanwhile, are both seeing an improvement in economic growth, which is largely domestically driven. This bodes well not only for sovereign debt, but also for credit in some sectors. Our EM credit teams particularly like green energy companies in this region, as well as infrastructure and transport in India and consumer companies in Indonesia. Financials should do well as strong economic growth translates into increased lending.

We are also seeing positive developments in some frontier markets. Nigerian authorities have recently harmonised the country’s myriad exchange rates, signalling a move to more focused and predictable monetary policy and a non-interventionist currency regime. They have also cut expensive fuel subsidies, raising the possibility of an improvement in Nigeria’s fiscal balances, which in turn should increase investor confidence and capital inflows into the country.

Zambia, meanwhile, has struck a breakthrough debt refinancing deal, and Ghana is expected to follow suit.

For now, we believe some of these opportunities are more compelling than those on offer in China itself, where a number of our portfolios are positioned more neutrally. We nonetheless think that in the medium term, China remains an important part of a diversified (EM) portfolio; its large domestic economy allows it to tailor-make policies uncorrelated to developments elsewhere in the world.

Currently, within China, we like the technology sector. There have been much more friendly policy signals recently after three years of regulatory crackdown. Conversely, we remain cautious on the real estate sector.

Overall, we believe China’s slowdown is manageable, especially as it has already triggered further support from authorities, with the trough likely behind us in Q2. Prospects for emerging market debt remain strong, with some attractive opportunities to be found within China and many more beyond it.

Important legal information

This marketing material is issued by Pictet Asset Management (Europe) S.A.. It is neither directed to, nor intended for distribution or use by, any person or entity who is a citizen or resident of, or domiciled or located in, any locality, state, country or jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, availability or use would be contrary to law or regulation. The latest version of the fund‘s prospectus, Pre-Contractual Template (PCT) when applicable, Key Information Document (KID), annual and semi-annual reports must be read before investing. They are available free of charge in English on www.assetmanagement.pictet or in paper copy at Pictet Asset Management (Europe) S.A., 6B, rue du Fort Niedergruenewald, L-2226 Luxembourg, or at the office of the fund local agent, distributor or centralizing agent if any.

The KID is also available in the local language of each country where the compartment is registered. The prospectus, the PCT when applicable, and the annual and semi-annual reports may also be available in other languages, please refer to the website for other available languages. Only the latest version of these documents may be relied upon as the basis for investment decisions.

The summary of investor rights (in English and in the different languages of our website) is available here and at www.assetmanagement.pictet under the heading "Resources", at the bottom of the page.

The list of countries where the fund is registered can be obtained at all times from Pictet Asset Management (Europe) S.A., which may decide to terminate the arrangements made for the marketing of the fund or compartments of the fund in any given country.

The information and data presented in this document are not to be considered as an offer or solicitation to buy, sell or subscribe to any securities or financial instruments or services.

Information, opinions and estimates contained in this document reflect a judgment at the original date of publication and are subject to change without notice. The management company has not taken any steps to ensure that the securities referred to in this document are suitable for any particular investor and this document is not to be relied upon in substitution for the exercise of independent judgment. Tax treatment depends on the individual circumstances of each investor and may be subject to change in the future. Before making any investment decision, investors are recommended to ascertain if this investment is suitable for them in light of their financial knowledge and experience, investment goals and financial situation, or to obtain specific advice from an industry professional.

The value and income of any of the securities or financial instruments mentioned in this document may fall as well as rise and, as a consequence, investors may receive back less than originally invested.

The investment guidelines are internal guidelines which are subject to change at any time and without any notice within the limits of the fund's prospectus. The mentioned financial instruments are provided for illustrative purposes only and shall not be considered as a direct offering, investment recommendation or investment advice. Reference to a specific security is not a recommendation to buy or sell that security. Effective allocations are subject to change and may have changed since the date of the marketing material.

Past performance is not a guarantee or a reliable indicator of future performance. Performance data does not include the commissions and fees charged at the time of subscribing for or redeeming shares.

Any index data referenced herein remains the property of the Data Vendor. Data Vendor Disclaimers are available on assetmanagement.pictet in the “Resources” section of the footer. This document is a marketing communication issued by Pictet Asset Management and is not in scope for any MiFID II/MiFIR requirements specifically related to investment research. This material does not contain sufficient information to support an investment decision and it should not be relied upon by you in evaluating the merits of investing in any products or services offered or distributed by Pictet Asset Management.

Pictet AM has not acquired any rights or license to reproduce the trademarks, logos or images set out in this document except that it holds the rights to use any entity of the Pictet group trademarks. For illustrative purposes only.