Select your investor profile:

This content is only for the selected type of investor.

Individual investors?

The myth of homo economicus

We are pleased to mark Richard Thaler’s Nobel Prize in economics by revisiting his speech at our annual client conference earlier this year.

From the South Sea Bubble in the 18th century to the US subprime mortgage crisis of 2008, the irrationality of human beings has been a persistent feature of investing.

And according to Professor Richard Thaler, a founding father of behavioural economics, irrational forces appear to be gathering strength once again – and in several areas of the financial system.

Take stock markets. Equities have raced to historic highs while their volatility has tumbled to its lowest level in almost 25 years. And all this in a year that has seen shocks like Brexit, Donald Trump entering the White House and the growing threat of a missile attack from a nuclear-armed North Korea.

“So what gives?” Mr Thaler asks. This disconnect, he explained, is yet another example of the flaws of the Efficient Markets Hypothesis (EMH), the idea that the market’s ups and downs follow a logical pattern. Under the theory, popularised by academics in the 1970s and now the intellectual underpinning of passive investing, stock prices instantly reflect all available information. In this framework, humans are rational participants who always make the ‘right’ decisions.

But to Thaler, who has spent the last 30 years dismantling EMH’s various assumptions, people cannot be more different from the utility-optimising ‘econs’ that inhabit the world created by the proponents of market efficiency. Because we are human, we have weaknesses, idiosyncrasies and biases – all of which draw us into making the wrong moves time and time again.

“We behave more like Homer Simpson…Markets have no way of transforming humans into econs,” he said.“Now the market has fallen asleep… yet the world looks really unpredictable

to me. We can make a long list of things that can go wrong.”

Investors see stocks rising but also think they're too expensive

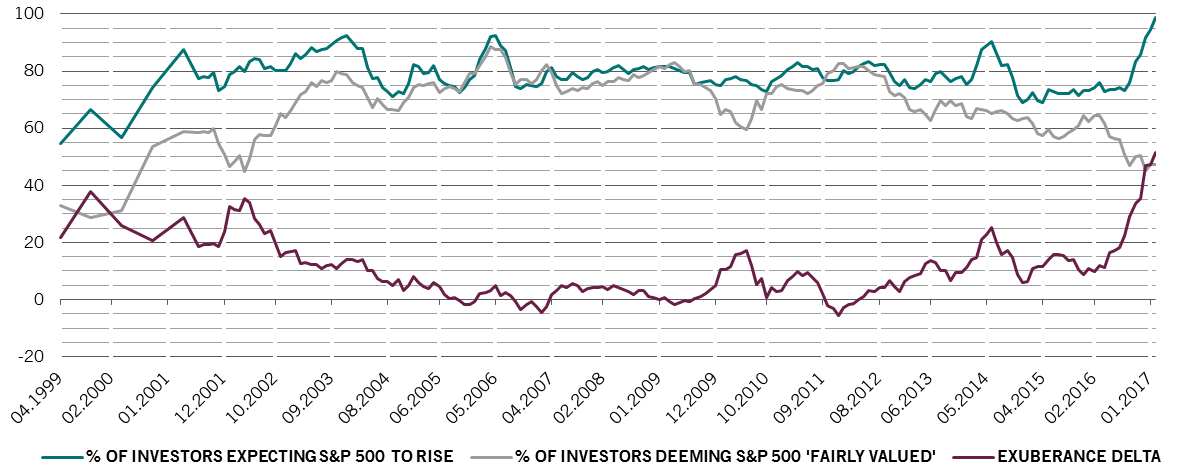

To demonstrate the market’s possible irrational exuberance, Thaler conducted an experiment with conference attendees. Each member of the audience was asked to predict the performance of the S&P 500 Index over the 12 months to May 2018. The average forecast was for a 10 per cent gain; the lowest forecast was for a return of 7 per cent.

“Investors think the market is overvalued and it’s going up – to me that’s pretty frightening…Looking at any measure, prices are high. I’m not forecasting a crash, but I’m more nervous than usual,” he said.

Valuations are lofty, Thaler reckons, partly because negative interest rates have triggered an unprecedented rush to buy risky assets, regardless of their price.

“People don’t know where to run, so they are staying with what they have on offer,” he said.

The 'hot hand' theory

Another possible behavioural explanation for the market’s steep rally is the ‘hot hand’. This theory describes how people on a winning streak convince themselves – and others considering copying them – that they can sustain this success well into the future. The theory was given the Hollywood treatment in 2015, when Thaler made a cameo appearance in The Big Short, an American film about the global financial crisis of 2008.It could be that managers they fire may have had a run of bad luck. Investment styles tend to go in and out of fashion. Plan sponsors hire and fire at the wrong time.

Interestingly, the hot hand doesn’t only apply to picking stocks. It has also been shown to apply to the selection of investment managers. Investors tend to choose asset managers based on their past performance. However, as a growing body of evidence demonstrates, this is no guarantee of future returns. Far from it.

When a pension fund fires a portfolio manager because of bad recent performance, the replacement tends to do worse than the predecessor, Thaler said.

“It could be that the managers they fire may have had a run of bad luck. Investment styles tend to go in and out of fashion. Plan sponsors fire and hire at the wrong time.”

To lessen the effect of the ‘hot hand’ in asset manager selection, investors need to be better at scrutinising returns. This means asking the right questions. “An investor needs to ask ‘what explains your excess returns? Why is it skill not luck and what evidence do you have that it works for the reasons you say it does?'"

Passive irrationality

Another more recent manifestation of irrationality, Thaler explained, is the growing popularity of passive investing.

Active managers have come under scrutiny as investors have grown frustrated by the high fees they have to pay even when the performance is disappointing. In 10 years to 2016, passive funds have attracted nearly USD 1.5 trillion of assets while the share of passive ownership in US stocks has reached 45 per cent.1

But while passive investment might be a rational choice for the individual investor, it makes no sense for the investment community as a whole, Thaler explained.

“If everyone is indexed, the market couldn’t be efficient because there would be nobody setting prices…”

Important legal information

This marketing material is issued by Pictet Asset Management (Europe) S.A.. It is neither directed to, nor intended for distribution or use by, any person or entity who is a citizen or resident of, or domiciled or located in, any locality, state, country or jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, availability or use would be contrary to law or regulation. The latest version of the fund‘s prospectus, Pre-Contractual Template (PCT) when applicable, Key Information Document (KID), annual and semi-annual reports must be read before investing. They are available free of charge in English on www.assetmanagement.pictet or in paper copy at Pictet Asset Management (Europe) S.A., 6B, rue du Fort Niedergruenewald, L-2226 Luxembourg, or at the office of the fund local agent, distributor or centralizing agent if any.

The KID is also available in the local language of each country where the compartment is registered. The prospectus, the PCT when applicable, and the annual and semi-annual reports may also be available in other languages, please refer to the website for other available languages. Only the latest version of these documents may be relied upon as the basis for investment decisions.

The summary of investor rights (in English and in the different languages of our website) is available here and at www.assetmanagement.pictet under the heading "Resources", at the bottom of the page.

The list of countries where the fund is registered can be obtained at all times from Pictet Asset Management (Europe) S.A., which may decide to terminate the arrangements made for the marketing of the fund or compartments of the fund in any given country.

The information and data presented in this document are not to be considered as an offer or solicitation to buy, sell or subscribe to any securities or financial instruments or services.

Information, opinions and estimates contained in this document reflect a judgment at the original date of publication and are subject to change without notice. The management company has not taken any steps to ensure that the securities referred to in this document are suitable for any particular investor and this document is not to be relied upon in substitution for the exercise of independent judgment. Tax treatment depends on the individual circumstances of each investor and may be subject to change in the future. Before making any investment decision, investors are recommended to ascertain if this investment is suitable for them in light of their financial knowledge and experience, investment goals and financial situation, or to obtain specific advice from an industry professional.

The value and income of any of the securities or financial instruments mentioned in this document may fall as well as rise and, as a consequence, investors may receive back less than originally invested.

The investment guidelines are internal guidelines which are subject to change at any time and without any notice within the limits of the fund's prospectus. The mentioned financial instruments are provided for illustrative purposes only and shall not be considered as a direct offering, investment recommendation or investment advice. Reference to a specific security is not a recommendation to buy or sell that security. Effective allocations are subject to change and may have changed since the date of the marketing material.

Past performance is not a guarantee or a reliable indicator of future performance. Performance data does not include the commissions and fees charged at the time of subscribing for or redeeming shares.

Any index data referenced herein remains the property of the Data Vendor. Data Vendor Disclaimers are available on assetmanagement.pictet in the “Resources” section of the footer. This document is a marketing communication issued by Pictet Asset Management and is not in scope for any MiFID II/MiFIR requirements specifically related to investment research. This material does not contain sufficient information to support an investment decision and it should not be relied upon by you in evaluating the merits of investing in any products or services offered or distributed by Pictet Asset Management.

Pictet AM has not acquired any rights or license to reproduce the trademarks, logos or images set out in this document except that it holds the rights to use any entity of the Pictet group trademarks. For illustrative purposes only.