How sovereign bond investors can help turn net zero into a reality

Government bonds sit at the outer reaches of the universe of climate-related investments. But it needn't be that way.

If the universe of environmental investments were the planetary systems within Star Wars, then sovereign bonds would surely be found in the outer rim territories. That’s because investors generally regard efforts to apply a climate lens to government debt as a hazardous voyage into the unknown.

The common refrain is that selecting - or excluding – specific sovereign bonds on the basis of a country’s environmental record compromises portfolio returns and does little to bring about changes in national climate policy.

Yet such a stance doesn’t survive contact with reality. Viewed from every conceivable angle, net zero will fail without public money and state intervention. The world needs trillions of dollars of government investment in climate mitigation and adaptation technology. And it also requires carefully crafted environmental laws and regulations.

All of which means that, as lenders to governments worldwide and holders of some USD128 trillion in sovereign debt, bond investors are in a unique position to influence both the financial and legislative sides of the climate ledger.

This explains why Pictet Asset Management has dedicated considerable resources in the past few years to develop an investment portfolio that places sovereign bonds at the heart of the net zero transition. Drawing on both quantitative and qualitative analysis, Pictet AM’s Climate Government Bond strategy seeks to identify – and allocate capital to - countries making the greatest strides in reducing carbon emissions.

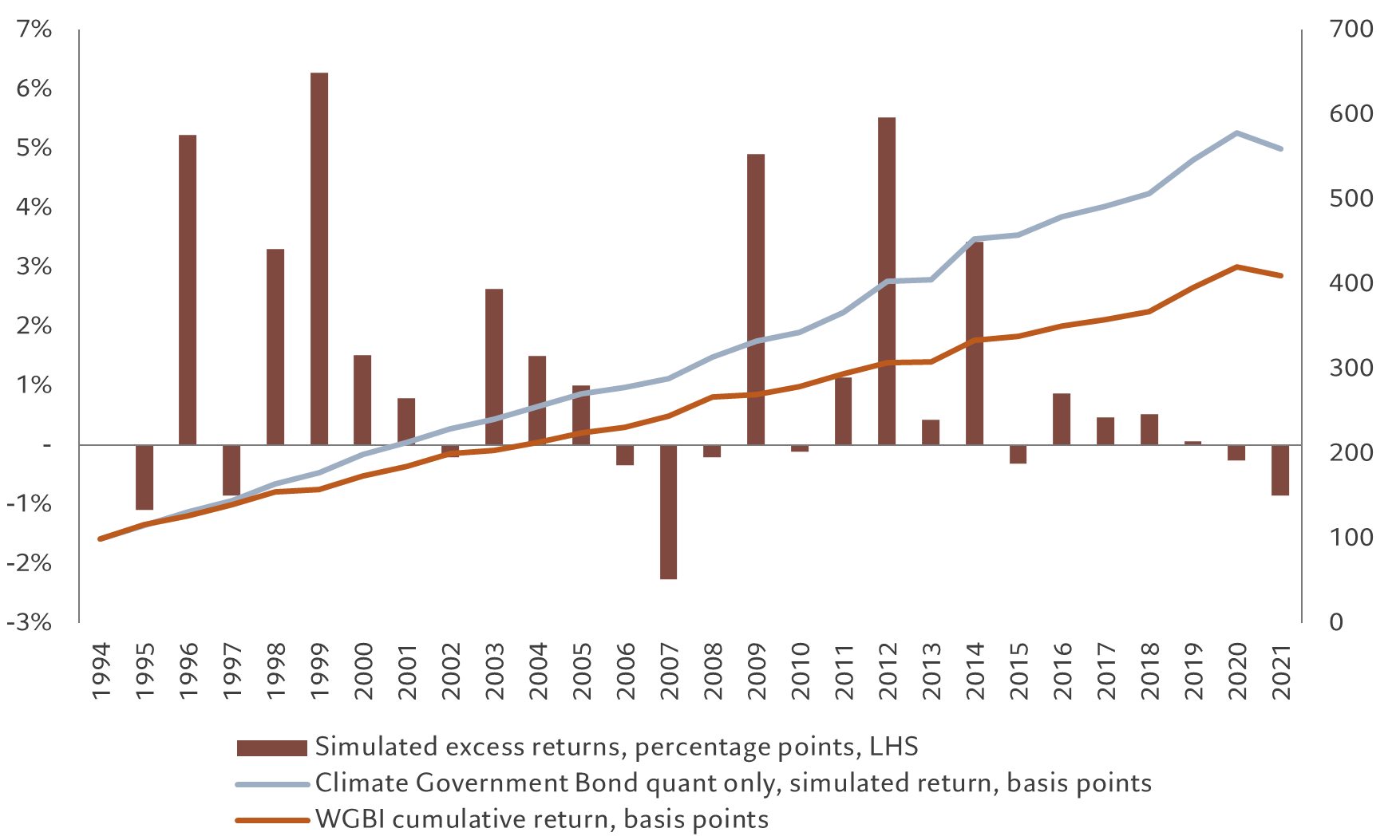

The strategy pursues twin objectives. It aims to build a fixed income portfolio that at least matches the returns and volatility of the FTSE World Government Bond Index but with a far smaller carbon footprint.

As lenders to governments worldwide and holders of some USD128 trillion in sovereign debt, bond investors are in a unique position to influence both the financial and legislative sides of the climate ledger.

The choice of carbon emissions as the singular investment reference point is a deliberate one. Carbon emissions have by far the most potent impact on global warming. They account for about 70 per cent of all greenhouse gas emissions and can linger in the atmosphere for hundreds of years.

Carbon dioxide is also the greenhouse gas upon which the vast majority of national net zero plans are based. Indeed, all of the 194 signatories of the Paris Climate Accord have specific emission reduction targets against which their net zero progress can be judged.

It also helps that emissions can be accurately measured and monitored. Thanks to technological advances and tighter environment regulations, carbon emissions data are now plentiful, reliable and frequently updated.

But having access to a wealth of accurate and timely data can be both a blessing and curse. Depending on how the data is parsed, it can give wildly different indications for portfolio construction. If, for example, bond investors chose to allocate capital simply on the basis of a country’s total carbon emissions, they would exclude bonds issued by China and the US.

If, however, the terms of reference were emissions per capita, then Chinese sovereign debt would score much more favourably – better, even, than either US Treasuries or Australian government bonds.

Using emissions data in such a crude way throws up another problem – it doesn’t offer a portal into the future. To avoid such pitfalls, we have devised a data framework that we believe gives a more accurate country by country comparison and can extrapolate past trends. Not every nation is covered by our analysis.

Instead, the screen assesses the carbon footprints of the 70 countries - all with liquid bond markets - that, together, account for 80 per cent of all carbon emissions. It incorporates two metrics. The first is a country’s total carbon emissions; the second is its total emissions divided by its annual economic output, an indicator of carbon efficiency. For each dataset, we analyse the trajectory over the past four-year period.

A distinguishing feature of the approach is how we calculate carbon emissions. Our data include emissions – and emissions reductions – that stem from industrial processes and changes in a country’s land management. It takes into account the complexities of the carbon cycle and how it is affected by soil erosion, deforestation and re-forestation.1

Beyond quantitative screens

This quantitative process has plenty to commend it. It provides a deep and broad analysis of a nation’s carbon footprint. Yet using it as the sole investment input would be ineffectual. Doing so creates a portfolio that is both too unstable and concentrated for most investors.

Our own analysis shows that a portfolio whose bond weightings were based entirely on our quantitative screen would be extremely vulnerable to, among other things, changes in economic conditions and abrupt moves in currencies and interest rates. Put differently, if investors were to use the carbon screen in isolation, their portfolio would return less and be more volatile than its reference benchmark.

Mitigating such risks is complicated. It requires a combination of qualitative judgement and sophisticated portfolio risk management techniques. Our assessment of Brazilian government bonds illustrates how the limitations of a systematic screen can be overcome.

Assessing the country’s carbon footprint solely through our quantitative screening, Brazil would have been included within the portfolio. It scores well on absolute carbon emissions and emissions per unit of GDP– the long term trends were positive in both cases. Yet those signals did not provide the full picture.

In breaking down the country’s carbon emissions by industry sector, it became clear that its performance was much weaker than first thought. Particularly troubling was the government’s poor management of its natural capital – in particular the Amazon ecosystem – and its excessive reliance on fossil fuels.

[Our] screen assesses the carbon footprints of 70 countries - all with liquid bond markets - that together account for 80 per cent of all carbon emissions.

Although wind power accounts for a sizeable proportion of Brazil’s total energy consumption, the government previously led by Jair Bolsonaro had favoured investments in oil and gas exploration over wind and solar. It has also ramped up fossil-fuelled power generation to combat hydropower shortages caused by droughts in 2021, and extended the life span of its coal-based power plants.

This bleak assessment was corroborated during the next phase of our qualitative assessment – an audit of Brazil’s policy framework based, in the first instance, on data provided by the consultancy Maplecroft and on discussions with members of the Climate Government Bond Strategy’s Advisory Board (AB).2

In evaluating the environmental policies proposed by the incoming administration of the centre-left president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, it became clear that it would take many years for Brazil to reverse the harm caused by earlier mis-steps.

AB members concluded that, that even if President Lula’s measures were put in place almost immediately, the existing damage done to the country’s natural capital would see its carbon emissions rise for years to come.

Portfolio optimisation and rebalancing

Similar observations was made in a recent study from the Bank for International Settlements.3 It found that government bond portfolios built using carbon footprint assessments alone leave investors exposed to potentially severe capital losses.

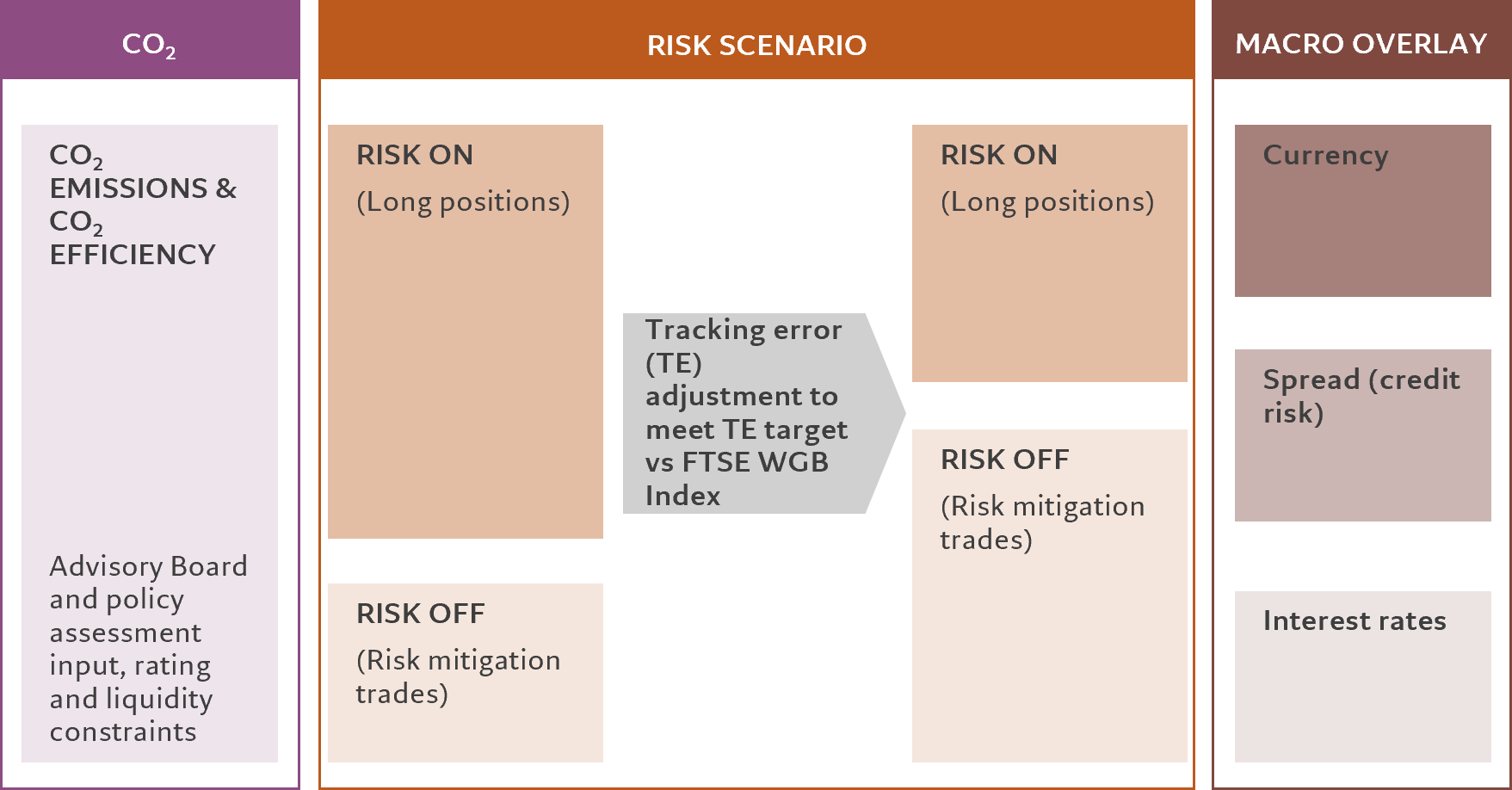

The optimisation process we deploy is designed to help our investment managers pursue their convictions without compromising the overall stability of the portfolio. A guiding principle is to ensure the portfolio is able to withstand the effects of abrupt moves in interest rates and currencies as well as any changes to a sovereign borrower’s credit standing. This is achieved by deploying a wide range of sophisticated risk management techniques and tools, including interest rate swaps, currency swaps and cross-currency basis swaps.

Portfolio rebalancing in practice: emerging market bonds

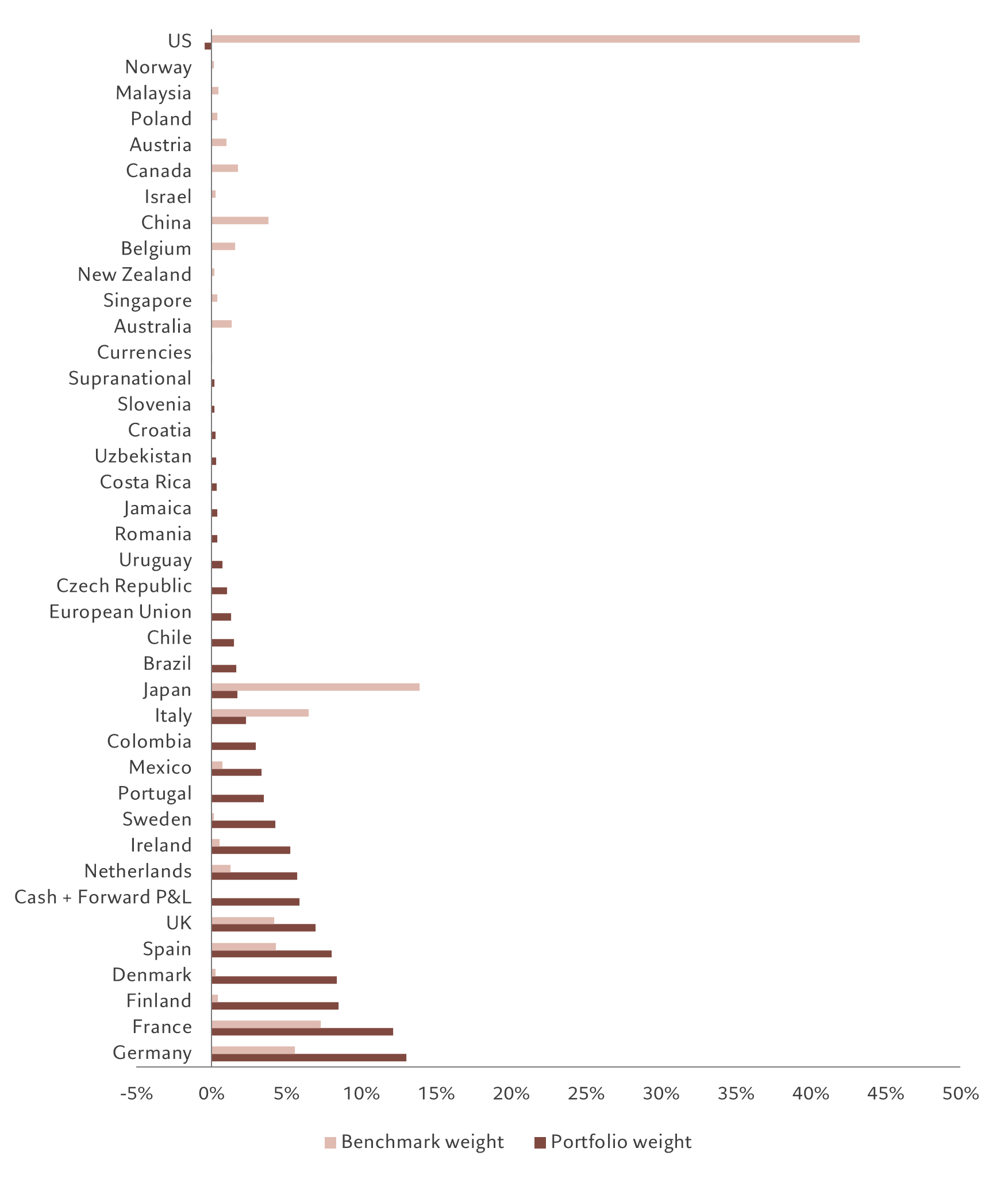

The calibration of our investments in emerging market sovereign bonds shows how the process works in practice. Emerging market debt features prominently in the portfolio because we find that many developing nations are making good progress in reducing their carbon footprints.

The problem is that, in allocating capital to these markets, the portfolio becomes inherently riskier than the reference benchmark, which is composed entirely of bonds issued by advanced economies.

To contain that risk but maintain the allocation, we enter into an offsetting trade, in this case a short position in emerging market currencies. With the hedge in place, any capital loss arising from the emerging market bond investment would be offset by a corresponding gain in the short currency position.

It is by adjusting risk and return dynamics in this way, we produce a net zero-aligned portfolio whose prospective return and tracking error more closely match those of its reference index.

Government bonds central, not peripheral, to net zero

References

[1] The calculations are based on the Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry (LULUCF) framework developed by the United Nations

[2] The Climate Bonds strategy’s Advisory Board, with whom portfolio managers meet twice times a year, is composed of experts in the fields of forestry and land management, climate change and the energy transition. The AB members are Professor Michael Köhl, head of the World Forest Institute at the University of Hamburg and professor for forest management, Dr Joeri Rogelj, director of research at the Grantham Institute at Imperial College, London and Professor Vaclav Smil, distinguished professor emeritus at the University of Manitoba, faculty of the environment. Additional country by country policy analysis is provided by other third parties including Maplecroft, a global risk and strategic consulting firm based in the UK.

[3] Gong, C., Jondeau, E. and Mojon, B., 2022. 'Building portfolios of sovereign securities with decreasing carbon footprints', Working Paper 1038, Bank for International Settlements.

Important legal information

This marketing material is issued by Pictet Asset Management (Europe) S.A.. It is neither directed to, nor intended for distribution or use by, any person or entity who is a citizen or resident of, or domiciled or located in, any locality, state, country or jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, availability or use would be contrary to law or regulation. The latest version of the fund‘s prospectus, Pre-Contractual Template (PCT) when applicable, Key Information Document (KID), annual and semi-annual reports must be read before investing. They are available free of charge in English on www.assetmanagement.pictet or in paper copy at Pictet Asset Management (Europe) S.A., 6B, rue du Fort Niedergruenewald, L-2226 Luxembourg, or at the office of the fund local agent, distributor or centralizing agent if any.

The KID is also available in the local language of each country where the compartment is registered. The prospectus, the PCT when applicable, and the annual and semi-annual reports may also be available in other languages, please refer to the website for other available languages. Only the latest version of these documents may be relied upon as the basis for investment decisions.

The summary of investor rights (in English and in the different languages of our website) is available here and at www.assetmanagement.pictet under the heading "Resources", at the bottom of the page.

The list of countries where the fund is registered can be obtained at all times from Pictet Asset Management (Europe) S.A., which may decide to terminate the arrangements made for the marketing of the fund or compartments of the fund in any given country.

The information and data presented in this document are not to be considered as an offer or solicitation to buy, sell or subscribe to any securities or financial instruments or services.

Information, opinions and estimates contained in this document reflect a judgment at the original date of publication and are subject to change without notice. The management company has not taken any steps to ensure that the securities referred to in this document are suitable for any particular investor and this document is not to be relied upon in substitution for the exercise of independent judgment. Tax treatment depends on the individual circumstances of each investor and may be subject to change in the future. Before making any investment decision, investors are recommended to ascertain if this investment is suitable for them in light of their financial knowledge and experience, investment goals and financial situation, or to obtain specific advice from an industry professional.

The value and income of any of the securities or financial instruments mentioned in this document may fall as well as rise and, as a consequence, investors may receive back less than originally invested.

The investment guidelines are internal guidelines which are subject to change at any time and without any notice within the limits of the fund's prospectus. The mentioned financial instruments are provided for illustrative purposes only and shall not be considered as a direct offering, investment recommendation or investment advice. Reference to a specific security is not a recommendation to buy or sell that security. Effective allocations are subject to change and may have changed since the date of the marketing material.

Past performance is not a guarantee or a reliable indicator of future performance. Performance data does not include the commissions and fees charged at the time of subscribing for or redeeming shares.

Any index data referenced herein remains the property of the Data Vendor. Data Vendor Disclaimers are available on assetmanagement.pictet in the “Resources” section of the footer. This document is a marketing communication issued by Pictet Asset Management and is not in scope for any MiFID II/MiFIR requirements specifically related to investment research. This material does not contain sufficient information to support an investment decision and it should not be relied upon by you in evaluating the merits of investing in any products or services offered or distributed by Pictet Asset Management.

Pictet AM has not acquired any rights or license to reproduce the trademarks, logos or images set out in this document except that it holds the rights to use any entity of the Pictet group trademarks. For illustrative purposes only.