[1] Climate Action Tracker

[2] https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/corporate-responsibility/sustainability/carbon-removal-program

[3] McKinsey

[4] https://www.ucl.ac.uk/global-governance/news/2021/jan/reforming-global-voluntary-market-carbon-offsets

[5] UCL/Trove and McKinsey

Select your investor profile:

This content is only for the selected type of investor.

Individual investors?

Negative emissions: going beyond net zero

To halt global warming, the world may have to go beyond achieving net zero and start actively removing carbon from the atmosphere.

As many as 140 countries and hundreds of companies around the world have joined the race to achieve net zero emissions, halt global warming and avert a climate crisis.

However, limiting temperature rises to 1.5C by 2100 – the cornerstone of the Paris Climate Agreement signed six years ago – remains a distant hope.

Current projections, based on policies already in place, show the world will be 2.7C warmer than it is today.1

And even in the best case scenario, which takes into account all the net zero pledges and promises, average temperatures are on course to rise by 1.8C.

The problem with net zero pledges as they stand is that not every industry can decarbonise at this pace.

“Net zero” is achieved when greenhouse gases pumped into the air are offset by removing the same amount of carbon from the atmosphere by other means.

To hit this goal by the middle of this century, every sector of the economy must reduce its greenhouse gas emissions.

Yet for industries such as agriculture, aviation, shipping and cement production, that is unrealistic. Their emissions are likely to remain high for decades. The same is true for large parts of the developing world. China and India will also not achieve net zero before 2060 and 2070, respectively, under their current targets.

This is where negative emissions technologies (NET), or methods to remove carbon from the atmosphere, could make a real difference.

According to Advisory Board members of Pictet AM's Timber and Global Environmental Opportunities strategies, scientists and governments increasingly see NET as vital to achieving net zero goals.

Already, companies such as software giant Microsoft and re-insurer Swiss Re are using NETs to remove CO2 gases.

New and innovative NETs such as direct air capture are attractive as they can be more efficient and can reduce the operating costs of removing carbon. This means they could potentially be deployed on a far wider scale.

Go negative, be positive

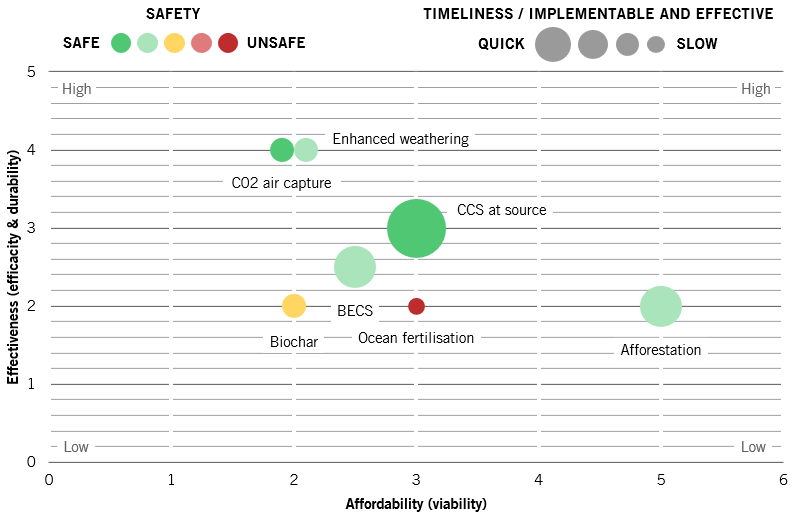

There are various ways to achieve negative emissions. But each solution comes with its own limitations, whether that is in terms of its effectiveness, durability and affordability.

Established NET methods such as the planting of trees rely on photosynthesis to absorb and lock in greenhouse gas, while emerging technologies such as carbon capture and storage (CCS) and enhanced weathering use chemistry to do much the same thing.

Afforestation is considered the most affordable method of removing CO2 from the atmosphere. At the same time, however, it scores less well on efficacy than other methods because it can take time for a newly planted forest to grow; its durability, meanwhile, hinges on the longevity of the forest itself. On the other hand, direct air capture technologies may be effective on installation but are currently very costly to implement.

Negative emissions technologies: the comparison

While businesses have an array of NET options to choose from, our Advisory Board members say that relying on just one technology may be less effective than a using a combination of different methods. In other words, using a portfolio of NETs can deliver a better overall outcome than deploying a single system in isolation (see Figure). The combinations will, naturally, vary by industry and by company.

For example, Microsoft looks to forestry for 85 per cent of its projected carbon removal, but also uses soil, bio-energy, bioc-char and direct air capture.2

Aiming to eliminate all its historic emissions since its founding in 1975, the Seattle-based firm has already purchased the removal of 1.3 million tonnes of carbon across 26 projects around the world.

Price of going negative

Surprisingly, it is the fossil fuel industry that is perhaps best equipped to harness NET. That's because some 90 per cent of its scientific, technological and engineering expertise is transferrable to the development of CCS technology.3

For other heavy emission industries such as agriculture or fashion, however, carbon removal technology is difficult to deploy at scale.

For these sectors, our experts say, a better solution could be the voluntary carbon market. This fledgling scheme, which operates outside regulated markets such as Europe’s Emissions Trading System, allows companies to offset their carbon emissions through the voluntary (as opposed to mandated) purchase of carbon removal credits.

The voluntary market is currently worth USD400 million but is expected to grow to as much as USD480 billion by 2050.4 This would equate to a drawdown of as much as 3.6 gigatonnes of CO2 equivalent (CO2e) a year, just under a fifth of the amount required by the Paris Accord.

Currently, the average voluntary carbon market price stands at around USD4-5 per tonne of CO2e. But industry estimates suggest could rise to as much as USD140 by 2050.5

In the short term at least, voluntary carbon market activities will be concentrated in land-based carbon-reduction tech, including afforestation, reforestation and improved forest management, which is both low cost and ready to implement. Over time, our Advisory Board members say, the market will expand to cover other emerging technologies, such as CCS.

But for the voluntary carbon market to take off, greater transparency is required. Not least in how offsets work.

For example, companies who buy carbon removal credits generated from afforestation should not expect to be able to apply the offsets immediately. In such cases, their use needs to somehow reflect the time lag between the point at which the carbon is released into the atmosphere to when it will be removed from a forest.

The world should use NETs as part of a broader portfolio of carbon-reduction measures designed to place the economy on a more sustainable footing.

No getting out of jail

For all the excitement around carbon offsetting, its expansion brings into sharp relief a thorny philosophical issue. If offsetting becomes the carbon-reduction tool of choice, it will do little to eradicate the activities that cause emissions in the first place.

Our Advisory Board members say NETs should not serve as some kind of “get out of jail free” card that allows polluters to avoid or delay efforts to cut emissions in the first place.

Rather, they say, NETs should instead form part of a broader portfolio of carbon-reduction measures designed to place the economy on a more sustainable footing.

Our Advisory Board members say NETs should not serve as some kind of “get out of jail free” card that allows polluters to avoid or delay efforts to cut emissions in the first place.

Rather, they say, NETs should instead form part of a broader portfolio of carbon-reduction measures designed to place the economy on a more sustainable footing.

more on thematic investing

The world needs a much higher carbon price

Carbon pricing has so far failed to take off. But it could soon become a pillar of the green economy.

June 2021

Hydrogen: beyond hot air

As production scales up and costs fall, a hydrogen-fuelled future is within sight.

January 2021

Adding thematic equities to diversified portfolios

Thematic equities are mainstream investments that investors can incorporate into their portfolios whatever their asset allocation framework.

September 2021

Important legal information

This marketing material is issued by Pictet Asset Management (Europe) S.A.. It is neither directed to, nor intended for distribution or use by, any person or entity who is a citizen or resident of, or domiciled or located in, any locality, state, country or jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, availability or use would be contrary to law or regulation. The latest version of the fund‘s prospectus, Pre-Contractual Template (PCT) when applicable, Key Information Document (KID), annual and semi-annual reports must be read before investing. They are available free of charge in English on www.assetmanagement.pictet or in paper copy at Pictet Asset Management (Europe) S.A., 6B, rue du Fort Niedergruenewald, L-2226 Luxembourg, or at the office of the fund local agent, distributor or centralizing agent if any.

The KID is also available in the local language of each country where the compartment is registered. The prospectus, the PCT when applicable, and the annual and semi-annual reports may also be available in other languages, please refer to the website for other available languages. Only the latest version of these documents may be relied upon as the basis for investment decisions.

The summary of investor rights (in English and in the different languages of our website) is available here and at www.assetmanagement.pictet under the heading "Resources", at the bottom of the page.

The list of countries where the fund is registered can be obtained at all times from Pictet Asset Management (Europe) S.A., which may decide to terminate the arrangements made for the marketing of the fund or compartments of the fund in any given country.

The information and data presented in this document are not to be considered as an offer or solicitation to buy, sell or subscribe to any securities or financial instruments or services.

Information, opinions and estimates contained in this document reflect a judgment at the original date of publication and are subject to change without notice. The management company has not taken any steps to ensure that the securities referred to in this document are suitable for any particular investor and this document is not to be relied upon in substitution for the exercise of independent judgment. Tax treatment depends on the individual circumstances of each investor and may be subject to change in the future. Before making any investment decision, investors are recommended to ascertain if this investment is suitable for them in light of their financial knowledge and experience, investment goals and financial situation, or to obtain specific advice from an industry professional.

The value and income of any of the securities or financial instruments mentioned in this document may fall as well as rise and, as a consequence, investors may receive back less than originally invested.

The investment guidelines are internal guidelines which are subject to change at any time and without any notice within the limits of the fund's prospectus. The mentioned financial instruments are provided for illustrative purposes only and shall not be considered as a direct offering, investment recommendation or investment advice. Reference to a specific security is not a recommendation to buy or sell that security. Effective allocations are subject to change and may have changed since the date of the marketing material.

Past performance is not a guarantee or a reliable indicator of future performance. Performance data does not include the commissions and fees charged at the time of subscribing for or redeeming shares.

Any index data referenced herein remains the property of the Data Vendor. Data Vendor Disclaimers are available on assetmanagement.pictet in the “Resources” section of the footer. This document is a marketing communication issued by Pictet Asset Management and is not in scope for any MiFID II/MiFIR requirements specifically related to investment research. This material does not contain sufficient information to support an investment decision and it should not be relied upon by you in evaluating the merits of investing in any products or services offered or distributed by Pictet Asset Management.

Pictet AM has not acquired any rights or license to reproduce the trademarks, logos or images set out in this document except that it holds the rights to use any entity of the Pictet group trademarks. For illustrative purposes only.