Select your investor profile:

This content is only for the selected type of investor.

Individual investors?

Demystifying inflation-linked bonds

With consumer prices ratcheting higher, investors are increasingly looking for products to protect them against inflation, like inflation-linked bonds. But they also need to be aware of the complexities.

April’s shock US consumer prices data made it clear that price pressures are starting to brew again. Whether higher inflation is baked into the fast rising economic cake or is just a temporary phenomenon is open to debate. But it’s little wonder investors are taking more notice of interest inflation protected – or index-linked – bonds.

That’s because the great fear for bond investors is unexpectedly strong inflation. Inflation itself is a fact of life that’s built into market prices. But shifts in inflation expectations can wreak havoc on fixed income portfolios. A big rise in what they think is likely to happen to consumer prices will cause investors to seek higher yields, thus pushing down bonds’ value.

At their simplest, the yields themselves are meant to compensate investors for lending their money over and above inflation. Normally that compensation is fairly modest for holding safe government bonds. In recent years it’s been wafer thin. So it doesn’t take a big rise in inflation expectations to eliminate years’ worth of returns. Hence the nervousness when, after years of deflationary trends, it looks like prices are starting to head higher again.

Index linked bonds exist to help investors minimise that risk. Although they’d been around in one form or another for centuries, they gained popularity in their modern form in the wake of the inflationary 1970s, with the UK government leading the way by creating index-linked gilts.

Tracking inflation

All bonds are issued with a principal, or par value – the value at which they will be redeemed when they mature. In the case of index linked bonds, the ultimate redemption price will be determined by the principal value plus cumulative inflation between now and then, usually calculated from an official index of consumer prices. As a simple example, if the par value of an index-linked bond maturing in ten` years’ time is 100 and the consumer price index has risen 30 per cent in the interim, investors can expect to receive 130 back from the borrower when the bond expires. And at each year along the way, the principal value of that bond will be adjusted according to what happened to inflation in that year.After years of deflationary trends, it looks like prices are starting to head higher.

That principal value, in turn, will determine the size of the annual coupon the investor receives. For instance, take a US Treasury index-linked bond with a ten year maturity that offers a 2 per cent interest rate. If in the first year there was 5 per cent inflation, the investor would have received a coupon of 2 per cent of USD105, or USD2.1. And if inflation rose at 3 per cent the following year, the principal value would be a little more than USD108, and the coupon would be 2 per cent of that. By the end of that 10th year, investors get 2 per cent of the new value, of USD130, which is to say USD2.6. An investor in an equivalent conventional bond with the same interest rate gets USD2 in the first year and USD2 in the last.

This simple picture is complicated by markets. The actual rate of interest that a bond investor gets depends on the price of the bond when the investor buys it, which only rarely and coincidentally will be the par value of, say, USD100. The coupon value is fixed against the par value in the case of conventional bonds or a function of par value plus accumulated inflation in the index-linked bond. That gives a notional yield. But the actual yield will vary according to the market price of the bond: when the bond price goes up, the yield (or rate of interest) goes down and vice versa.

Breaking down the breakevens

Because investors tend to be able to easily switch between government-issued index-linked bonds and their equivalent conventional bonds, if the price of one starts to look attractive relative to the other, they will sell the latter and buy the former until the prices are in balance again.

The difference in yields between index-linked and conventional bonds of the same maturity is what’s known as the breakeven rate. The rule of thumb is that the breakeven rate is the implied market expectation for inflation during the lifetime of the bond.

In the simplified version, the breakeven is the average rate at which consumer prices need to change during the lifetime of the bonds for them to offer investors an equivalent return. If inflation runs hotter than expected, index-linked bonds will prove to have been the better asset, and vice versa.

So, for instance, if the yield on a nominal, or conventional bond is 1.50 per cent and the yield on an index linked bond is 0 per cent, the break-even inflation rate would imply 1.5 per cent average annual inflation until the bonds mature.

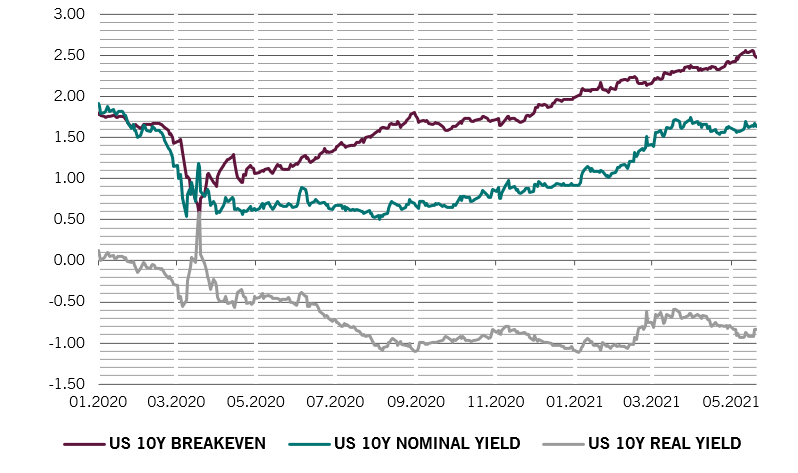

Real, nominal and breakeven rates for US 10-year bonds, percentage points

But the story is usually more complex than that, which means the breakeven rate doesn’t always reflect actual market inflation expectations. For instance the yield on nominal bonds will also contain built-in insurance against the risk that inflation will run hotter than people expect – ie. the inflation risk premium. When inflation has been steady for a long time, this premium is likely to be very small. But as data become increasingly volatile, it becomes a bigger component of yield.

Meanwhile, because there are considerably fewer index-linked bonds in circulation than conventional issues, there is an illiquidity premium that is factored into their yields. Normally this relative lack of market liquidity isn’t apparent. But during times of market crisis it can become significant.

These, in turn, can cause the apparent inflation breakeven rate to be distorted. Inflation uncertainty can push the breakeven rate well above other measures of inflation expectations. A surge in the liquidity premium can, in turn, cause the breakeven rate to collapse suggesting an impending future of persistent deflation – as happened in March 2020 when the Covid pandemic triggered a general liquidity crisis in the markets.

In other words, for the breakeven rate to accurately reflect expected inflation, the illiquidity premium and inflation risk premium have to be exactly equal. They rarely are.

An alternative measure of inflation expectations

Given that breakevens aren’t an entirely reliable way of measuring inflation expectations, it’s useful to have other measures. One is to look at inflation swaps.

In essence, an inflation swap is a contract in which one party (the payer) makes fixed interest payments over a defined period, where the payments are based on inflation expectations when the agreement is struck. On the other side of the contract, the counterparty (the receiver) makes payments to the payer that are based on the actual rate of inflation over the period of the contract.

So the payer will thus want actual inflation to run hotter than initially expected for the term of the contract while the receiver will want it to be lower. In this way, the market’s expected rate of inflation can be gauged. The most popular of these swaps is the five-year, five-year forward rate (5y5y) which measures what the market expects five year inflation expectations will be in five years’ time – in other words an indication of the markets’ long run inflation expectations.

Financial repression

All of this is important to bear in mind when considering what’s been happening in the bond markets over the past year.

A move up in US yields in 2020 was largely driven by a rise in breakeven rates, at a time when real rates remained deeply negative across the spectrum of US Treasury bond maturities, also known as the yield curve. The Federal Reserve’s central bankers were content with this. Negative real yields are supportive of the economy, while the rise in breakevens spoke of expectations that inflation would start to rise, subject to the above caveats. And rising inflation implies a narrowing of the gap between the economy’s potential growth and the actual growth rate, at the time well below potential.

At a time when the Fed remains worried about the vulnerability of the economy to a relapse, rising real yields are a concern.

That rise in bond yields has continued. But since around the turn of the year, most of that move has come not from rising breakeven rates, but from rising real yields (see Fig. 1). At a time when the Fed remains worried about the vulnerability of the economy to a relapse, rising real yields are a concern. That’s because they raise the cost of borrowing: both for the government, which has a huge and rising burden of debt, and for corporations.

In effect, what the Fed is seeking to do is to transfer resources from lenders to borrowers by keeping real interest rates as negative as possible – something that’s known as financial repression. Rising real yields put the economic burden on borrowers instead. To stave this off, the Fed is likely to keep monetary conditions easy for some time to come.

Financial repression has been very effective in the past. For instance, in the wake of the huge debt burden the UK build up during the Second World War, the government held down the cost of servicing those debts by keeping nominal interest rates at low levels while promoting growth and inflation through loose monetary policy, effectively turning real interest rates negative. The effect is plain in the data. In 1945 the stock of UK government debt was worth 216 per cent of GDP. By 1955, that proportion had dropped to 138 per cent. It stands as a warning to bond investors and another reason to take an interest in index-linked securities.

Important legal information

This marketing material is issued by Pictet Asset Management (Europe) S.A.. It is neither directed to, nor intended for distribution or use by, any person or entity who is a citizen or resident of, or domiciled or located in, any locality, state, country or jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, availability or use would be contrary to law or regulation. The latest version of the fund‘s prospectus, Pre-Contractual Template (PCT) when applicable, Key Information Document (KID), annual and semi-annual reports must be read before investing. They are available free of charge in English on www.assetmanagement.pictet or in paper copy at Pictet Asset Management (Europe) S.A., 6B, rue du Fort Niedergruenewald, L-2226 Luxembourg, or at the office of the fund local agent, distributor or centralizing agent if any.

The KID is also available in the local language of each country where the compartment is registered. The prospectus, the PCT when applicable, and the annual and semi-annual reports may also be available in other languages, please refer to the website for other available languages. Only the latest version of these documents may be relied upon as the basis for investment decisions.

The summary of investor rights (in English and in the different languages of our website) is available here and at www.assetmanagement.pictet under the heading "Resources", at the bottom of the page.

The list of countries where the fund is registered can be obtained at all times from Pictet Asset Management (Europe) S.A., which may decide to terminate the arrangements made for the marketing of the fund or compartments of the fund in any given country.

The information and data presented in this document are not to be considered as an offer or solicitation to buy, sell or subscribe to any securities or financial instruments or services.

Information, opinions and estimates contained in this document reflect a judgment at the original date of publication and are subject to change without notice. The management company has not taken any steps to ensure that the securities referred to in this document are suitable for any particular investor and this document is not to be relied upon in substitution for the exercise of independent judgment. Tax treatment depends on the individual circumstances of each investor and may be subject to change in the future. Before making any investment decision, investors are recommended to ascertain if this investment is suitable for them in light of their financial knowledge and experience, investment goals and financial situation, or to obtain specific advice from an industry professional.

The value and income of any of the securities or financial instruments mentioned in this document may fall as well as rise and, as a consequence, investors may receive back less than originally invested.

The investment guidelines are internal guidelines which are subject to change at any time and without any notice within the limits of the fund's prospectus. The mentioned financial instruments are provided for illustrative purposes only and shall not be considered as a direct offering, investment recommendation or investment advice. Reference to a specific security is not a recommendation to buy or sell that security. Effective allocations are subject to change and may have changed since the date of the marketing material.

Past performance is not a guarantee or a reliable indicator of future performance. Performance data does not include the commissions and fees charged at the time of subscribing for or redeeming shares.

Any index data referenced herein remains the property of the Data Vendor. Data Vendor Disclaimers are available on assetmanagement.pictet in the “Resources” section of the footer. This document is a marketing communication issued by Pictet Asset Management and is not in scope for any MiFID II/MiFIR requirements specifically related to investment research. This material does not contain sufficient information to support an investment decision and it should not be relied upon by you in evaluating the merits of investing in any products or services offered or distributed by Pictet Asset Management.

Pictet AM has not acquired any rights or license to reproduce the trademarks, logos or images set out in this document except that it holds the rights to use any entity of the Pictet group trademarks. For illustrative purposes only.