[1] On average stock returns are about 10 percentage points higher in November-April half-year periods than in May-October half-year periods. The Sell in May effect is pervasive in financial markets. Andrade S. V. Chhaochharia M. Fuerst “'Sell in May and Go Away' Just Won’t Go Away". Financial Analysts Journal Forthcoming (SSRN 2115197) 18.03.2013.

[2] Swinkels L. van Vliet P. “An Anatomy of Calendar Effects” Journal of Asset Management 13(4) 2012 pp. 271-286.

[3] “There’s still only one winner in the growth versus value fight” Financial Times 20.10.2018 https://www.ft.com/content/dda25e30-d383-11e8-a9f2-7574db66bcd5

Select your investor profile:

This content is only for the selected type of investor.

Institutions & Sub-Advisory?

Demystifying equity factors

Factor investing has become increasingly popular. Here's what it is and how it works.

Who hasn’t heard “sell in May and go away”? The market adage is as old as the hills. But it keeps cropping up because by and large, it’s tended to work. Over the long run, in liquid, mature equity markets like the US and UK, investors have generally improved their returns by reducing their allocation to stocks during the summer months and increasing it from around Halloween.1

This seasonal effect is a basic example of an investment factor – specific attributes shared by groups of assets that have historically had a material impact on investment performance. Some, like “sell in May”, are simple rules that have persisted for many decades. Others, such as the tendency for smaller cap stocks to deliver stronger returns over the long run, are more cyclical and complex.

factory prices

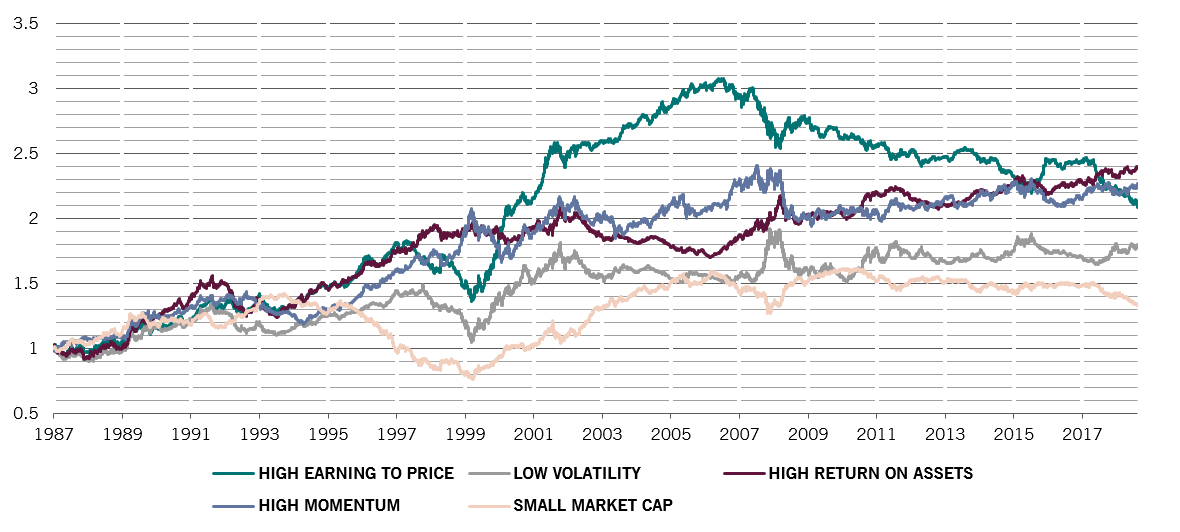

Factor performance relative to MSCI World*

Over the past 50 years, a large volume of academic work has sought to identify factors that can reliably be harnessed by investors. In effect, factors are market anomalies that contradict the efficient market hypothesis, which argues that all relevant information is reflected in asset prices.

Yet while factors may be the preserve of professional investors, understanding why they exist can provide useful insights into market inefficiencies, investor psychology and portfolio construction.

Some factors, for example, owe their existence to investors’ behavioural biases – such as loss aversion or self-perpetuating faddishness. Others, meanwhile, hold only during certain stages of a business cycle. Some are arbitraged away almost as soon as they’re identified and others exist because of the regulatory constraints certain investors are subject to – such as having to match liabilities with low-risk assets.

A universe of factors

The range of factors is broad. Take calendar effects, where the “sell in May…” rule is only one of a number of seasonal factors. There’s also the Santa Claus rally, where equities tend to surge in the week after Christmas and into the start of the new year, not to mention quarter-end and turn-of-month effects that have variously been identified.2

Investment professionals, however, tend most often to focus on five key factors [see chart above for examples].

Size: in the early 1980s, Rolf Banz, long associated with Pictet Asset Management, analysed and described a relationship between companies’ market capitalisations and their risk adjusted returns. Over time, he found that smaller companies tended to outperform. This may be down to liquidity effects – investors demand more premium from shares that, potentially, they can’t easily sell. Or it may be down to the fact that smaller companies are less researched, creating inefficiency that investors can take advantage of.

Valuation: companies whose shares trade on lower price-to-earnings multiples, or price-to-book ratios, tend to outperform over the very long run. One argument for this is that over shorter periods market noise can mask firm's intrinsic value, but that eventually shares will revert to the correct price. However, this sort of mis-pricing can last a long time. In the 10 years since the global financial crisis, growth stocks have outpaced their value equivalents. It could take a recession for this to reverse.3

Momentum: the tendency for stocks that are enjoying a strong run to continue this into the future. Under a momentum strategy, investors increase their allocation to stocks or bonds that have been rising in price, and cut holdings of those that are dropping. Momentum has historically tended to be a particularly effective investment approach, though getting caught out on big market turning points can be painful.

Quality: companies with strong profit margins and significant market share tend to outperform over the long run. Quality is similar to valuation, and has similar drawbacks. Stock markets can under-appreciate good quality companies for uncomfortably long stretches.

Volatility: portfolios composed of stocks that are less volatile than average tend to generate better returns over time than those composed of shares that see big price swings. Generally, investors would expect to be compensated for risk – for which volatility is a proxy. Evidence, however, suggests the opposite.

The benefits of diversity

Some factors only become apparent after considerable data crunching. Quantitative strategists often analyse hundreds of millions of data points across tens of thousands of data series ranging across market prices, government statistics and private sector surveys to identify a source of additional returns. Some of these factors will then only work for a short time before the entire market catches on.

By identifying factors and exploiting them appropriately, investors can boost their returns above the market average. Equity factors can also serve as portfolio building blocks.

An equity portfolio that deliberately splits investments across say, value, growth and low volatility stocks can be as diversified as one that invests by region or by country. That's because 'value', 'growth' and 'low volatility' stocks outperform during different phases of the economic cycle.

By identifying factors and exploiting them appropriately, investors can boost their returns.

But as with all aspects of investing, factors aren't failsafe. Some are dependent on the investment time horizon and can contradict each other over a given period – for instance a company with an attractive valuation can grow even cheaper if momentum happens to be holding sway. Others hold on average over many cycles but don’t during shorter spans. Some factors work for a time but then fade as they become adopted widely.

Understanding why some factors have persisted historically is crucial for investors seeking to apply these strategies. So too is being able to assess how popular such trades have become when implementing factor approaches. Meanwhile, some factors only exist on paper, as a result of heavy data mining and back testing.

What is clear is that factors of one sort or another are likely to be cited and used by investors as long as markets continue to exist.

related articles

Demystifying credit default swaps

Used responsibly and judiciously credit derivatives can help reduce the risks that come with bond investing.

January 2018

Demystifying alternative investments

Alternatives are prized by investors. They're also in short supply.

March 2018

Demystifying sustainable investing

There's much more to responsible investing than avoiding "sin" stocks. And it can make financial sense too.

April 2019

Important legal information

This marketing material is issued by Pictet Asset Management (Europe) S.A.. It is neither directed to, nor intended for distribution or use by, any person or entity who is a citizen or resident of, or domiciled or located in, any locality, state, country or jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, availability or use would be contrary to law or regulation. The latest version of the fund‘s prospectus, Pre-Contractual Template (PCT) when applicable, Key Information Document (KID), annual and semi-annual reports must be read before investing. They are available free of charge in English on www.assetmanagement.pictet or in paper copy at Pictet Asset Management (Europe) S.A., 6B, rue du Fort Niedergruenewald, L-2226 Luxembourg, or at the office of the fund local agent, distributor or centralizing agent if any.

The KID is also available in the local language of each country where the compartment is registered. The prospectus, the PCT when applicable, and the annual and semi-annual reports may also be available in other languages, please refer to the website for other available languages. Only the latest version of these documents may be relied upon as the basis for investment decisions.

The summary of investor rights (in English and in the different languages of our website) is available here and at www.assetmanagement.pictet under the heading "Resources", at the bottom of the page.

The list of countries where the fund is registered can be obtained at all times from Pictet Asset Management (Europe) S.A., which may decide to terminate the arrangements made for the marketing of the fund or compartments of the fund in any given country.

The information and data presented in this document are not to be considered as an offer or solicitation to buy, sell or subscribe to any securities or financial instruments or services.

Information, opinions and estimates contained in this document reflect a judgment at the original date of publication and are subject to change without notice. The management company has not taken any steps to ensure that the securities referred to in this document are suitable for any particular investor and this document is not to be relied upon in substitution for the exercise of independent judgment. Tax treatment depends on the individual circumstances of each investor and may be subject to change in the future. Before making any investment decision, investors are recommended to ascertain if this investment is suitable for them in light of their financial knowledge and experience, investment goals and financial situation, or to obtain specific advice from an industry professional.

The value and income of any of the securities or financial instruments mentioned in this document may fall as well as rise and, as a consequence, investors may receive back less than originally invested.

The investment guidelines are internal guidelines which are subject to change at any time and without any notice within the limits of the fund's prospectus. The mentioned financial instruments are provided for illustrative purposes only and shall not be considered as a direct offering, investment recommendation or investment advice. Reference to a specific security is not a recommendation to buy or sell that security. Effective allocations are subject to change and may have changed since the date of the marketing material.

Past performance is not a guarantee or a reliable indicator of future performance. Performance data does not include the commissions and fees charged at the time of subscribing for or redeeming shares.

Any index data referenced herein remains the property of the Data Vendor. Data Vendor Disclaimers are available on assetmanagement.pictet in the “Resources” section of the footer. This document is a marketing communication issued by Pictet Asset Management and is not in scope for any MiFID II/MiFIR requirements specifically related to investment research. This material does not contain sufficient information to support an investment decision and it should not be relied upon by you in evaluating the merits of investing in any products or services offered or distributed by Pictet Asset Management.

Pictet AM has not acquired any rights or license to reproduce the trademarks, logos or images set out in this document except that it holds the rights to use any entity of the Pictet group trademarks. For illustrative purposes only.