[1] MSCI China index in local currency, data covering period 01.01.2023 – 16.10.2023

[2] EPFR Global and JP Morgan, 06.10.2023

[3] Refinitiv, data covering period 31.04.2008 - 31.03.2023

[4] Bloomberg, data as of 25.10.2023

[5] Shanghai Stock Exchange State-Owned 100 index and MSCI China, data covering period 01.01.2023 – 07.08.2023

[6] Refinitiv, data as of 16.10.2023

Chinese stocks: turning the corner?

Chinese stocks, however unloved they maybe now, should remain a strategic part of global investors' portfolios.

From high hopes to disappointment, investors in China’s equity markets have had a rollercoaster year.

The country’s sudden re-opening from Covid lockdowns in January was widely hailed as a watershed moment. It raised hopes of a consumer spending boom that would revitalise corporate profits, marking an end to years of lacklustre earnings growth.

Yet this optimistic scenario didn’t play out.

China is now flirting with deflation, households are holding on to their savings, and consumer spending remains below its pre-crisis six-year trend. We now expect the economy to grow 5 per cent this year compared to the 6 per cent initially projected. Investors may therefore feel tempted to shift out of China altogether.

Chinese stocks are in any case among the very few not to have enjoyed double digit returns so far this year.1

The market is shunned even by investors focused on emerging markets, with the typical fund holding less than the benchmark allocation in Chinese equities.2

Yet the truth is China remains too big for investors to ignore.

There are several reasons why Chinese stocks should be considered a strategic allocation for global portfolios.

It is a world leader in several key transformational industries, it is home to a growing consumer market and its economy is on course to become the world’s largest in less than a decade.

By the same token, nobody should expect a rapid change in China Inc’s fortunes. Developments that would improve Chinese stocks’ return on equity will emerge only very gradually over the next five years.

This means investors would be better served by steadily rebuilding positions in a selected number of industries, focusing on those which Chinese authorities consider strategic priorities.

High growth, low earnings

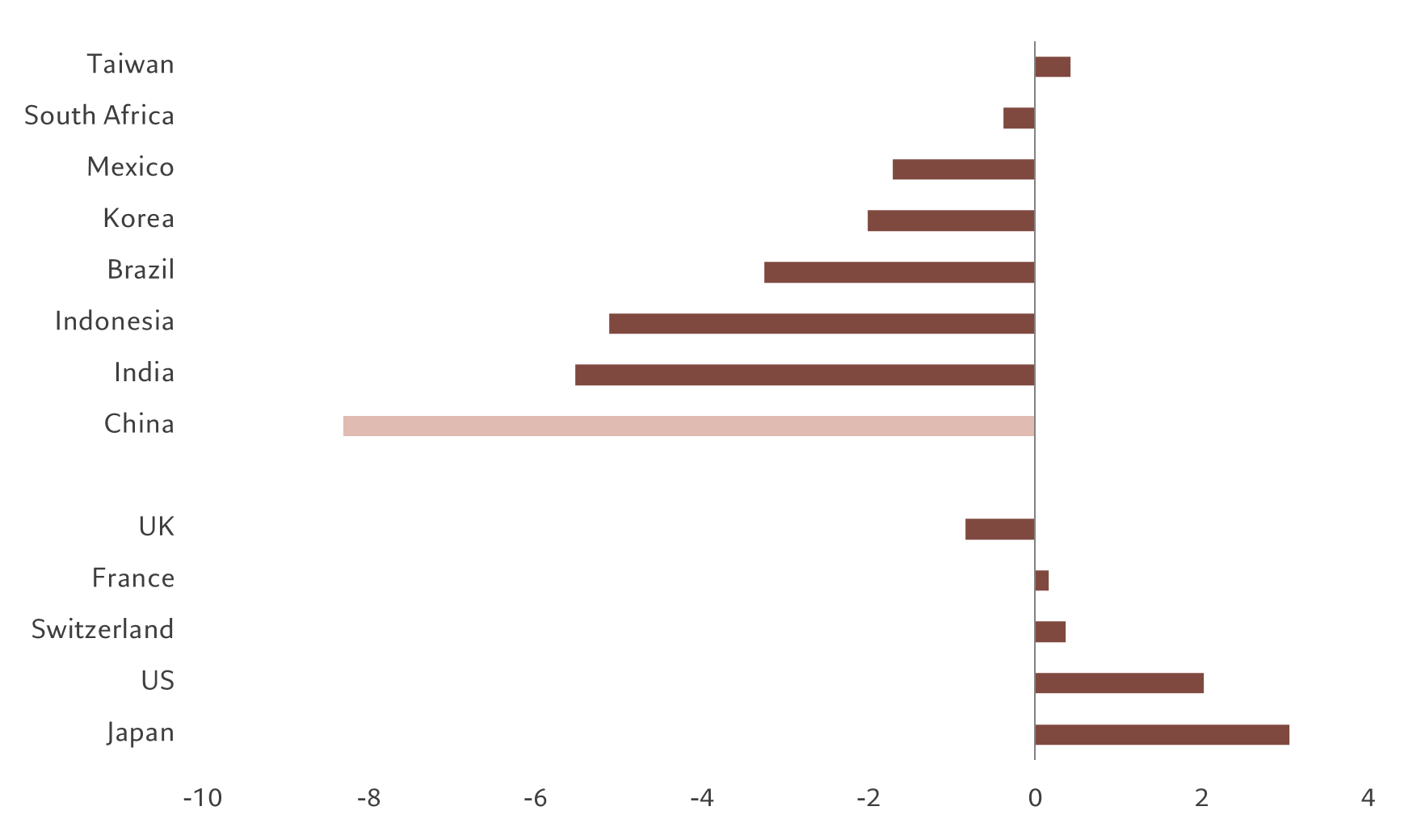

Although China and other emerging markets have registered stronger GDP growth than advanced economies in recent years, their corporate earnings have lagged those of their richer counterparts by a considerable margin.

Chinese firms have scored particularly poorly.

The compounded annual growth rate of Chinese firm’s earnings per share has undershoot the country’s economic growth by a hefty 8 percentage points in the past 15 years, double the average shortfall for emerging markets.3

This also compares unfavourably with the US, where profits have grown faster than the economy by 2 percentage points over the same period.

China, an earnings outlier

Gap between corporate earnings growth and GDP growth, annualised, percentage points (16-year), by country

(Almost) an end of regulatory tumult

China’s historic failure to translate GDP growth into earnings growth has several causes.

A volatile regulatory environment, equity dilution and weak governance have each had a part to play in pegging back corporate profits.

Yet there are grounds to believe these headwinds could ease somewhat over the next several years.

Regulation is the thorniest problem facing corporations and their shareholders.

China has introduced structural reforms aimed at engineering sustained and balanced growth, steering clear of the credit-fuelled investment binge of the past few years.

But accompanying this shift has been Beijing’s tendency to enact sudden regulatory crackdowns on industries it considers have become too powerful.

The 2-1/2 year-long clampdown, involving flagship companies from industries ranging from technology and education to finance and gaming including Alibaba, Tencent and Didi Chuxing, has wiped more than USD1 trillion off the stock market value and impaired companies’ ability to grow their earnings.

But encouragingly for investors, there are signs of an easing of tensions between the private sector and state authorities.

Chinese companies are streamlining their businesses and making themselves more resilient in the face of slowing economic growth... their self-help measures are paying off.

In July, the People’s Bank of China hit Alibaba affiliate Ant Group with a nearly USD1 billion fine for violating various regulations, raising hopes that a possible end to the regulatory deluge will allow it to secure a financial holding company licence and revive its plans for a stock market listing.

In the same month, Beijing also pledged to improve conditions for private businesses, outlining more than 30 measures that included promises to treat private companies the same as state-owned enterprises, consult more with entrepreneurs on drafting policies, and cut market entry barriers for firms.

Chinese companies, on their part, are streamlining their businesses and making themselves more resilient in the face of slowing economic growth.

Many have tightened their control on operational expenses, which in return improved operating margin and profit growth.

The most recent interim result season confirmed a trend which started last year where the bottom-line growth has been much better than the top line growth, especially among large Internet companies and consumer companies, illustrating how their self-help measures are paying off.

Buyback vs dilution

Equity investors in China have always had to contend with the issue of dilution – a common feature of many emerging markets where companies going through a growth spurt issue new or additional shares to finance expansion, which in turn reduces the relative ownership of existing shareholders and hence dilutes earnings per share.

China has seen a particularly strong equity dilution among emerging peers – we estimate the sale of secondary shares from companies represented in the country’s main equity benchmark has reduced earnings per share by some 2 per cent per year.

But Chinese authorities appear keen to alleviate this pressure. The country’s securities regulator has revised rules to make it easier for listed companies to buy back shares and "actively safeguard their investment value and protect the interest of smaller shareholders".

It also unveiled a package in August aimed at supporting share buybacks and encouraging long-term investment. More than 30 companies including technology and online healthcare firms have already announced plans to buy back shares.

The pace of IPO has also slowed down sharply in the past two years, with the value of total announced deals falling to just RMB51 billion in the first 10 months of the year, compared with nearly RMB1 trillion in 2021.4

We also see an encouraging development on the country’s efforts to overhaul its gigantic state-owned enterprises (SoEs), which should improve the outlook for corporate profits.

Beijing is stepping up efforts to guide SoEs – which represent nearly a third of the benchmark index – to become leaner, improve profitability and shareholder returns and communicate better with investors in a revamp that could trigger a rerating of the sector and boost visibility of future cashflows.

The government also added “lifting the dividend payout ratio” as one of the key performance indicators for SoEs, which should also benefit minority shareholders.

Investors are certainly becoming more optimistic. Mainland-listed state firms – which represent nearly a third of the benchmark CSI300 index – have outperformed the broader market this year, with China Mobile gaining 47 per cent this year and China Mobile and PetroChina over 50 per cent.

The index of 100 SoEs has managed to remain flat this year, comparing favourably with the broader index which has lost 10 per cent.5

These state-owned firms – from telecom operators to resource and industrial companies – also have a competitive advantage over others as Beijing wants them to play a central role in meeting its goal of establishing self-reliance in strategic industries such as semiconductor, robotics or environmental technology.

Prosperity over profitability

Despite all these positive developments, certain factors that have hindered profitability of China Inc are sure to remain a feature of the investment landscape over the coming years.

Take geopolitics. Political tensions involving China are likely to persist, or even intensify, as many governments try to gain economic independence and self-sufficiency in strategically important sectors key to safeguarding future growth.

In such a fast-changing environment full of unforeseen risks and surprises, investors must realise that Chinese assets are not suited to a passive buy-and-forget approach.

Instead, they should embrace an active approach, where they constantly monitor developments and stand ready to change courses quickly. We think investors should be especially aware of risks from the following areas:

The US-China relationship. An improvement in the relationship with the two economic powers over trade and technology would boost potential GDP growth of China, while drastically reducing the risk premium embedded in the current discount. The two countries have restarted their talks again with Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen visiting Beijing in July and Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo in August. But years of deepening mistrust will not disappear overnight. We need to see a tangible progress, such as a removal of export restrictions, to significantly change our view on China. We don’t think this is likely in the coming years, with some of the curbs being embedded in recent flagship legislations such as the Inflation Reduction Act.

Strategic objectives. China’s quest for self-reliance in key strategic technologies, such as decarbonisation, defence security and semiconductor, may represent a wealth of profitable opportunities for companies operating in these industries. This, however, comes at the expense of profitability and shareholder returns of non-aligned sectors and their investors. Sectors such as healthcare will be subject to further volatility. Beijing’s efforts to eradicate rampant graft and bribery in drug sales practices has triggered losses of over 15 per cent for the sector – an albeit small part of the benchmark at just over 6 per cent.6

Common prosperity. While the latest bout of regulatory crackdowns may have eased, what is not changing is this long-standing policy objective which triggered such moves in the first place. This Communist Party slogan, which prioritises social and economic equity over corporate profits, has gained more prominence under President Xi Jinping. The government has used common prosperity to justify its tight grip over the corporate sector and rein in “disorderly expansion of capital”. The equitable prosperity goal has played a part in stifling innovation and supressing dynamism of Corporate China in recent years. While some adjustments may happen, we don’t think Beijing would abandon this policy course in the coming years.

China within a global equity portfolio

China is a market that should remain a key feature of a global equity portfolio, both for the opportunities it presents and for diversification benefits.

But in order to effectively capitalise on the Asian powerhouse’s economic potential, investors in the country’s stock markets have to be discerning.

While China’s macroeconomic fundamentals may face some challenges in the near term, we find more encouraging developments among individual companies.

The higher risk premium on China – mainly as a result of macroeconomic uncertainty and geopolitical concerns – have weighed on multiples, but this has in turn opened up attractive opportunities from a valuation standpoint.

In the coming five years, we expect Chinese equities to deliver what can only be described as a modest return of some 7 per cent per year, stripping out the foreign exchange effect.

Such a return, and the prospect of Chinese stocks continuing to trade at a sizeable discount to developed world equities, suggests that the market’s “beta” could prove an unreliable source of return.

Investors, therefore, should seek out companies with a strong balance sheet, sustainable pricing power and attractive valuation in sectors that are aligned with Beijing’s policy priorities.

more on china and other emerging markets

China’s economic challenges and emerging market bonds: no need for panic

China may be slowing down, but we believe that doesn’t diminish the opportunities on offer in emerging market debt. Here is why.

August 2023

A new dawn for Indian stocks

Corporate India's promising fundamentals mean the country's equity market is poised to outpace that of its emerging market peers.

September 2023

Premium brands welcome China's revival

China's luxury goods market is set to benefit from considerable pent-up demand as the country emerges from its Covid lockdowns.

February 2023

Secular outlook 2023

Securing single-digit annual returns from a diversified portfolio could prove an unusually complex task in the next five years, largely because of volatile inflation and more muscular state intervention.

June 2023

Important legal information

This marketing material is issued by Pictet Asset Management (Europe) S.A.. It is neither directed to, nor intended for distribution or use by, any person or entity who is a citizen or resident of, or domiciled or located in, any locality, state, country or jurisdiction where such distribution, publication, availability or use would be contrary to law or regulation. The latest version of the fund‘s prospectus, Pre-Contractual Template (PCT) when applicable, Key Information Document (KID), annual and semi-annual reports must be read before investing. They are available free of charge in English on www.assetmanagement.pictet or in paper copy at Pictet Asset Management (Europe) S.A., 6B, rue du Fort Niedergruenewald, L-2226 Luxembourg, or at the office of the fund local agent, distributor or centralizing agent if any.

The KID is also available in the local language of each country where the compartment is registered. The prospectus, the PCT when applicable, and the annual and semi-annual reports may also be available in other languages, please refer to the website for other available languages. Only the latest version of these documents may be relied upon as the basis for investment decisions.

The summary of investor rights (in English and in the different languages of our website) is available here and at www.assetmanagement.pictet under the heading "Resources", at the bottom of the page.

The list of countries where the fund is registered can be obtained at all times from Pictet Asset Management (Europe) S.A., which may decide to terminate the arrangements made for the marketing of the fund or compartments of the fund in any given country.

The information and data presented in this document are not to be considered as an offer or solicitation to buy, sell or subscribe to any securities or financial instruments or services.

Information, opinions and estimates contained in this document reflect a judgment at the original date of publication and are subject to change without notice. The management company has not taken any steps to ensure that the securities referred to in this document are suitable for any particular investor and this document is not to be relied upon in substitution for the exercise of independent judgment. Tax treatment depends on the individual circumstances of each investor and may be subject to change in the future. Before making any investment decision, investors are recommended to ascertain if this investment is suitable for them in light of their financial knowledge and experience, investment goals and financial situation, or to obtain specific advice from an industry professional.

The value and income of any of the securities or financial instruments mentioned in this document may fall as well as rise and, as a consequence, investors may receive back less than originally invested.

The investment guidelines are internal guidelines which are subject to change at any time and without any notice within the limits of the fund's prospectus. The mentioned financial instruments are provided for illustrative purposes only and shall not be considered as a direct offering, investment recommendation or investment advice. Reference to a specific security is not a recommendation to buy or sell that security. Effective allocations are subject to change and may have changed since the date of the marketing material.

Past performance is not a guarantee or a reliable indicator of future performance. Performance data does not include the commissions and fees charged at the time of subscribing for or redeeming shares.

Any index data referenced herein remains the property of the Data Vendor. Data Vendor Disclaimers are available on assetmanagement.pictet in the “Resources” section of the footer. This document is a marketing communication issued by Pictet Asset Management and is not in scope for any MiFID II/MiFIR requirements specifically related to investment research. This material does not contain sufficient information to support an investment decision and it should not be relied upon by you in evaluating the merits of investing in any products or services offered or distributed by Pictet Asset Management.

Pictet AM has not acquired any rights or license to reproduce the trademarks, logos or images set out in this document except that it holds the rights to use any entity of the Pictet group trademarks. For illustrative purposes only.